Seminarians received as candidates to Holy Orders

On October 26, 2022, four Mount Angel seminarians were received as candidates for Holy Orders during Mass in the Abbey church. The monastic community welcomed Archbishop Alexander K. Sample of Portland, Oregon, as the principal celebrant for the Mass. Other bishops concelebrated the Mass together with Abbot Jeremy Driscoll, OSB, seminary chancellor, Msgr. Joseph Betschart, president-rector, vocation directors, visiting priests, and priests from the seminary and monastery.

On October 26, 2022, four Mount Angel seminarians were received as candidates for Holy Orders during Mass in the Abbey church. The monastic community welcomed Archbishop Alexander K. Sample of Portland, Oregon, as the principal celebrant for the Mass. Other bishops concelebrated the Mass together with Abbot Jeremy Driscoll, OSB, seminary chancellor, Msgr. Joseph Betschart, president-rector, vocation directors, visiting priests, and priests from the seminary and monastery.

During the homily, Archbishop Sample encouraged the four candidates to continue their final preparation before ordination to the transitional diaconate and later priesthood. “We rejoice with you today, that the Lord has called you to labor in his harvest out of the compassion of Jesus for the crowds, and that God, like Jeremiah, has been forming you from all eternity for this vocation,” he said. After the homily, Archbishop Sample, on behalf of his brother bishops, received the seminarians’ declaration of intent to complete their preparation for Holy Orders and “to give faithful service to Christ the Lord and his Body, the Church.”

Those received as candidates included Anthony Shumway, Diocese of Salt Lake City; Maximiliano Muñoz, Archdiocese of Seattle; James Ladd, Archdiocese of Portland; Michael Williams, Diocese of Las Vegas. The rite of candidacy “makes all these years of praying to follow the will of God in my life come to a point where I can say, yes, I truly want to give my life to the Church if she will have me,” shares Shumway. For Muñoz, the liturgical rite “takes up the ministries we have been exercising in past years, synthesizes them, and puts them in relationship to our dioceses, to the Churches we hope one day to serve with our whole lives.”

Please pray for these new candidates and all the seminarians studying at Mount Angel Seminary. “May God who has begun the good work in [them] bring it to fulfillment.”

– Ethan Alano

Categories: Seminary, Uncategorized

On the evening of September 8, the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the monks of Mount Angel Abbey gathered in Mount Angel Abbey’s church to celebrate the Mass of Simple Profession for two novices, Brody Stewart and Fr. Jack Shrum. The novices professed vows of obedience, stability, and conversion of life for a period of three years.

On the evening of September 8, the Feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the monks of Mount Angel Abbey gathered in Mount Angel Abbey’s church to celebrate the Mass of Simple Profession for two novices, Brody Stewart and Fr. Jack Shrum. The novices professed vows of obedience, stability, and conversion of life for a period of three years. The congregation filled the church and joined the monks in song and prayer, interceding for the men about to profess monastic vows.

The congregation filled the church and joined the monks in song and prayer, interceding for the men about to profess monastic vows. Seminarians and students, faculty, staff, and other guests gathered with the monastic community in the Abbey church on August 22 to celebrate the opening of the new academic year at Mount Angel Seminary with the Mass of the Holy Spirit.

Seminarians and students, faculty, staff, and other guests gathered with the monastic community in the Abbey church on August 22 to celebrate the opening of the new academic year at Mount Angel Seminary with the Mass of the Holy Spirit. Mount Angel Seminary’s 33 graduates concluded the academic year with both the Baccalaureate Mass and Commencement Exercises celebrated on April 30 at 8 am and 10 am, respectively, in the Abbey church. In addition to graduates, many friends and family with smiling faces filled the church as a hopeful sign of better days ahead.

Mount Angel Seminary’s 33 graduates concluded the academic year with both the Baccalaureate Mass and Commencement Exercises celebrated on April 30 at 8 am and 10 am, respectively, in the Abbey church. In addition to graduates, many friends and family with smiling faces filled the church as a hopeful sign of better days ahead. Though he was only 50 at the time of his death, Fr. Stuart Long led a big, adventurous life. As a high school student athlete in Montana, he excelled at wrestling and football. He continued with football at Carroll College in Helena, where he discovered his passion for boxing, winning the state Golden Gloves heavyweight title in 1985.

Though he was only 50 at the time of his death, Fr. Stuart Long led a big, adventurous life. As a high school student athlete in Montana, he excelled at wrestling and football. He continued with football at Carroll College in Helena, where he discovered his passion for boxing, winning the state Golden Gloves heavyweight title in 1985. At a Mass celebrated in the church at Mount Angel Abbey on February 23, 2022, six seminarians were instituted as lectors and six as acolytes. Together, the men represented eight dioceses and one religious community.

At a Mass celebrated in the church at Mount Angel Abbey on February 23, 2022, six seminarians were instituted as lectors and six as acolytes. Together, the men represented eight dioceses and one religious community. Nine seminarians studying at

Nine seminarians studying at  The 28 students of Mount Angel Seminary’s graduating class of 2021 ended the year with a Baccalaureate Mass in the Abbey church on April 23, followed by Commencement the following morning. “This was a year like no other” was a sentiment often heard throughout the two services.

The 28 students of Mount Angel Seminary’s graduating class of 2021 ended the year with a Baccalaureate Mass in the Abbey church on April 23, followed by Commencement the following morning. “This was a year like no other” was a sentiment often heard throughout the two services.

Deacon Cheeyoon Timothy Chun, Diocese of Orange; Deacon Joshua Falce, Diocese of Boise; Deacon Tony Galati, Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon; Franklin Ubochioma Iwuagwu, Archdiocese of Santa Fe; Deacon Val Park, Archdiocese of Seattle; Br. Israel Sanchez, O.S.B., Mount Angel Abbey; Deacon Jordan Taylor Sánchez, Archdiocese of Santa Fe; and Br. Joseph Mary Tran, O.C.D., Order of Discalced Carmelites, each received their Master of Divinity from the Seminary’s Graduate School of Theology.

Deacon Cheeyoon Timothy Chun, Diocese of Orange; Deacon Joshua Falce, Diocese of Boise; Deacon Tony Galati, Archdiocese of Portland in Oregon; Franklin Ubochioma Iwuagwu, Archdiocese of Santa Fe; Deacon Val Park, Archdiocese of Seattle; Br. Israel Sanchez, O.S.B., Mount Angel Abbey; Deacon Jordan Taylor Sánchez, Archdiocese of Santa Fe; and Br. Joseph Mary Tran, O.C.D., Order of Discalced Carmelites, each received their Master of Divinity from the Seminary’s Graduate School of Theology.

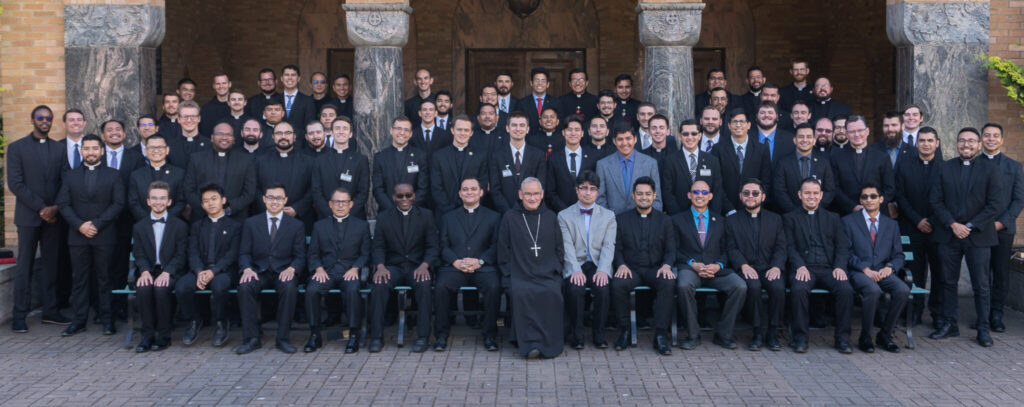

It was with great joy that Mount Angel Seminary celebrated the Mass of Candidacy for 11 seminarians in the Abbey church on the morning of October 22, 2020.

It was with great joy that Mount Angel Seminary celebrated the Mass of Candidacy for 11 seminarians in the Abbey church on the morning of October 22, 2020.